Some books are simply meant to be reread again and again. My well-loved copy of Ella Enchanted attests to this fact. With its wrinkled spine and its pages crisp with age, the novel is made more magical with each life milestone we’ve shared together. This year marks the book’s twenty-fifth birthday and the third time I’ve reached that “happily ever after.” I have now stepped into Ella’s adventures as a child, a teen, and an adult.

Cursed with obedience by a foolish fairy, Ella is forced to obey any command given to her, no matter how harmful or ridiculous. Her acts of rebellion cause body-wrenching headaches that compel her to submit. Ella must continually use her cleverness and courage to protect herself as people intentionally and unintentionally command her to do things against her will.

I’ve revisited this book time and time again because it speaks to an inner fire I’ve always struggled to name in myself. Perhaps it’s in Ella’s conviction to be true to her own heart, no matter what others or society might wish for her. Maybe it’s her rebellious and contrarian spirit, her desire to turn conversations into playful sparring matches. Whatever it is, every chapter exudes passion—passion for friendship, for kind mothers, for adventure, for humor, for justice, for life. Gail Carson Levine remains one of my greatest influences as a fantasy writer, helping to inspire my love for magical curses and romances between emotional equals. Those themes also appear in Levine’s The Two Princesses of Bamarre and her Princess Tales series, which I equally adore.

Most of all, the story’s details stand out in my memory—certain flashes of thread in the larger tapestry that stay in motion. These are the moments that taught me, from a young age, ways to live and love. I’ve distilled them into a tonic of five life lessons I’ve learned from Ella Enchanted. (Plot spoilers below!)

Romance Doesn’t Mean an Endless Honeymoon

When we talk about “fairy-tale romance,” we usually picture a couple staring into each other’s eyes longingly, never wanting to spend a second apart. At the giants’ wedding, Fairy Lucinda bestows that very “gift” to the newlyweds so that they can go nowhere without each other. Naturally, the bride and groom are distraught, but Lucinda believes that couples who are in love are immune to pet peeves and quarrels. Another fairy in attendance tells her wryly, “If they argue—and all loving couples argue—they’ll never be alone to recollect themselves, to find ways to forgive each other.”

Ella’s fairy-tale romance with Char is similarly grounded in realism. There’s a moment when Ella reflects that the prince sometimes rambles too much in his letters about topics that don’t interest her, but she doesn’t mind. She doesn’t expect him to be the mirror image of herself. They don’t need to share every interest or partake in every quirk. Ella and Char have a healthy relationship because of their shared respect and admiration for each other’s independence. They each pursue their own adventures separate from the other. And when their paths converge, they’re more eager than ever to search for secret passageways together or go sliding down the banisters of old castles.

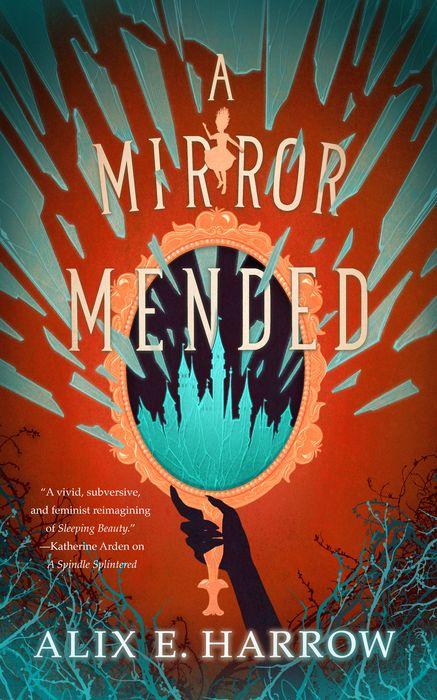

Buy the Book

A Mirror Mended

As a preteen obsessed with love and romance, these moments of realism were oddly reassuring. The pedestal of romance that always seemed to loom so high, up in the clouds and out of reach, now felt like a platform I could potentially step onto, an achievable aim. It meant that I didn’t have to be perfect every second of the day in order to be loved. I didn’t want to foist that burden of perpetual perfection on my partner, either.

The third time I read Ella Enchanted, I read it with my husband. We were both touched by the letters that Ella and Char write to each other because that’s how we fell in love, too—writing long-distance messages. Before we met in person, we wrote about all the physical flaws we thought we had and whispered our most shameful secrets in late-night phone calls. I didn’t share his love of baseball, and he didn’t share my love of books (yet), but we felt comfortable gabbing about them anyway because we knew the other person wouldn’t mind indulging us.

Too often, I think, we’re quick to dismiss potential partners for so much as sneezing in a way we dislike (my husband does sneeze at a decibel dangerous to humans), as if those details signal some deeper incompatibility. In reality, it’s a sign of real closeness that—like Char in his letters to Ella—we’re comfortable sharing our flaws, knowing we won’t be loved less for them. We’re not striving to follow some ideal of coupledom, where we’re forever dancing in perfect sync—it’s okay to accidentally stomp on each other’s toes from time to time.

Language Is a Bridge Toward Understanding

Ella’s greatest talent is her knack for languages. She can repeat any word in a foreign tongue with ease, which allows her to forge meaningful connections with anyone she meets. At finishing school, she befriends an Ayorthaian girl who’s delighted to teach Ella her native language. With the elves, she returns their hospitality by speaking a little Elfian, and combined with gestures and laughter, they “cobbled together a language understood by all.” She comforts a gnome child in his language and tricks a fairy by pretending to be from another land.

Her understanding of other cultures even saves her from danger. When she’s captured by hungry ogres, she pays attention not only to what they say but how they say it. Using a tone that’s both honeyed and oily, she convinces them not to eat her. More than that, she understands ogre psychology and that their greatest fear is missing out on an even bigger meal—a fact which Ella plays to her advantage.

Any time we show a willingness to learn and engage in someone’s language, we extend a kind of empathy. Our interest, curiosity, and readiness to learn and be curious will likely be met with kindness in return. Even with the ogres, Ella charms them with her sense of humor and buys herself more time. Although I lack Ella’s skill for learning languages, I love studying them and discovering how words and expressions give insight into culture.

Around the same time I was first building my Gail Carson Levine collection, I started taking Japanese classes. All through my teens, I was intent on becoming fluent and visiting Japan someday. That dream fell by the wayside in college, but last year, I dusted off my Japanese textbooks, attended virtual conversation events, and visited my local Japanese market. I can’t describe the strange joy I felt at a baseball game recently when a fan held up a sign in Japanese for her favorite player and I realized I could read it. We were two strangers, but we were connected by that shared understanding.

In Ella’s world, the Ayorthaian nobles are often people of few words, except when they sing. Yet these customs are never treated as inferior in any way to her own Kyrrian traditions. Their differences simply create a beautiful wideness to the world, and I’ve found that our own reality operates in much the same way. Learning Japanese made me aware of the importance of using honorific speech and of bowing to convey respect, which gave me further insight into the culture and the way people interact. With every place I travel, I want to be like Ella and learn at least a few phrases, along with the cultural etiquette necessary to communicate courteously.

We’re All Cursed with Obedience

Many people struggle to say no—that’s especially the case for many women, because society trains them to be agreeable and self-sacrificing. For Ella, saying no is a literal impossibility thanks to her curse. She attends finishing school under her father’s orders. Hattie and Olive—two nasty bullies in her social circle—take her money and her mother’s pearl necklace. Hattie even deprives Ella of food for days by commanding her not to eat. Even worse, Hattie demands that Ella put an end to her only real friendship. Later on, her stepmother orders her to become a scullery maid and wash the floors. And Ella does, scrubbing until her knuckles bleed.

One reason this novel speaks so deeply to young readers is because it captures a hallmark of being a teenager: the tug-of-war between obedience and rebellion. Really, that desire to be transgressive exists throughout our lives, to some degree. We want the freedom to break the rules, yet we feel compelled to follow them because the consequences for doing otherwise are too great. We could be left unloved, penniless, and disowned if we fail to follow certain scripts we’ve been given. I think of kids with musical or artistic ambitions who become lawyers instead because their parents demand it, or because conventional wisdom says they’re destined for failure.

I’m cursed with obedience as well. When a stranger asks me for a favor—to edit something, maybe, or give advice—I have a hard time ignoring that request. But this realization has helped me recognize how others are cursed with obedience, too, and how easy it is to accidentally take advantage of their willingness to give.

My mom, for example, has an incredibly generous spirit. It’s a running joke with my husband that we can’t visit my parents’ house without having a pair of socks or a bag of gummy worms thrust into our arms. I grew up feeling that no gift was too large to ask for, whether it was a trip to New York City or a new MacBook—the last of which I actually requested for Christmas one year. However, as she handed it over with a regretful look, I felt utterly terrible because of course she hadn’t really wanted to spend a small fortune on one gift.

From that point onward, I vowed never to take advantage of anyone else’s generosity. I don’t want to be like Hattie or Olive in making demands I know someone will feel compelled to obey. I don’t want to let anyone walk all over me, either. Like Ella running away from finishing school, I do my best to steer clear of the people and institutions that demand my obedience.

Well-Meaning People Make Mistakes

Sometimes we think we’re acting for the good of someone else, but really we’re only acting out of our own self-interest. As the novel opens, “That fool of a fairy Lucinda did not intend to lay a curse on me. She meant to bestow a gift.” Lucinda truly believes she’s bestowing wonderful, amazing spells that better the lives of the recipients. She tells Ella that she should “be happy to be blessed with such a lovely quality” as obedience. It’s not until another fairy challenges Lucinda to spend three months being obedient herself that she understands the painful truth—her kindness is actually torture.

Lucinda’s character arc is a beautiful thing to behold. Not only does she get her “comeuppance” in experiencing her own curses firsthand, but she expresses genuine regret, and she changes her behavior as a result. No more “gifts” of obedience or couples being forced to love each other. She (mostly) drops her self-centered, attention-seeking persona and becomes more authentic and empathetic.

I once wanted to surprise a friend who wasn’t feeling well by having random artists send her funny cards and gifts. I hadn’t considered that my friend would be upset by the idea of me giving out her address to strangers. We talked extensively on the phone afterward, but that experience made me realize that things I was comfortable with weren’t necessarily in keeping with someone else’s boundaries. I thought I was giving her a gift when I was actually bestowing a curse.

The solution comes down to empathy and humility. As well-intentioned as someone’s actions might be, if it hurts or bothers the person they were trying to help, then they need to ask themselves, “Was I doing this for them or for me? Was I assuming I knew what they needed when they didn’t ask for that?”

We don’t have to spend three months as a squirrel to understand that being a woodland creature wouldn’t be entirely fun. Empathy isn’t just “How would I feel if I were in their situation?” but also “How would I feel if I were them in this situation?” In my friend’s shoes, I would’ve been happy to receive surprise gifts, even from internet strangers. But she is not me, and I am not her. A person can’t truly know what it’s like to be someone else unless they’ve tried to be them, which goes beyond walking a stretch in their seven-league boots.

Willpower Comes from Within

In the end, Ella makes the powerful choice to reject Char’s marriage proposal—not because she doesn’t love him but because she desperately wishes to protect him. If they were married, others could command her to kill him, and she’d forever be handing her wealth over to her greedy family.

This is what finally breaks her curse of obedience. Her love for Char allows her to obey her own heart instead of what others want for her. She saves her prince and herself through a willpower she digs deep to find:

“For a moment I rested inside myself, safe, secure, certain, gaining strength. In that moment I found a power beyond any I’d had before, a will and a determination I would never have needed if not for Lucinda, a fortitude I hadn’t been able to find for a lesser cause. And I found my voice.”

Willpower involves pushing through challenges as well as controlling our impulses and emotions. Sometimes this results in repressing our true selves instead of setting them free.

As a high schooler, my impulse was to always project a certain image of myself. I’d lie about the music I was listening to because it was “cool” to like AC/DC and Tool but not Avril Lavigne and J-Pop. I felt embarrassed about expressing my love for fan fiction, romance, and other supposedly “girly” interests for fear of attracting scorn. I never openly called myself a feminist—despite believing in it strongly—because I knew that feminism was associated with negative qualities, at least among my peers.

Even though I was surrounded by countless people who were proud of their interests and embraced a broad spectrum of what it means to be a woman, I struggled to share in that pride. Feminist novels like Ella Enchanted helped reinforce the message that feminine qualities are valuable and valid and not confined to any one interpretation, but it was only through digging deep within myself that I found my voice. In adulthood, I developed the willpower to confront and overwrite my own internalized misogyny (although there’s always more work to do there). Instead of giving in to that impulse to present a “cool girl” version of myself, I finally have the courage and confidence to say, “Romance is a vital and profound genre, and if you feel the need to belittle it, I’m not going to be quiet about the reasons you’re wrong.”

After all, fairy tales aren’t just fiction—they are a way of seeing the world.

Diane Callahan spends her days shaping stories as a writer and developmental editor. Her YouTube channel, Quotidian Writer, provides practical tips for aspiring authors.